|

| The arrival of the First Fleet in Sydney in 1788. Also the transportation of convicts. (Source: http://nla.gov.au/nla.pic-an7891482) |

Accompanied by the arrival of the First Fleet, a group of unwanted British convicts landed on Australia. In 1788, 11 vessels were loaded with convicts arrived the port of Botany Bay. Since then, the first generation of white Australian settled down and ushered in a new age of Australia. Such kind of convicts transportation endured 100 years from 1788 to 1888. At the first place, mainly the eastern continent of Australia and Tasmania demanded a large number of convicts to forge the new-born colonial society. With the exploration and occupation of the western and southern Australia, convicts had been sent to these regions correspondingly. During the later time of transportation, one outstanding feature was more skilled convicts were transported and they all specilised in different industries. This reflects the desire of a new colony to develop a new society. It was also the eastern states that first abolished the transportation of convicts by 1840s. With a duration of 100 years' transportation, around 160,000 convicts set foot on Australia. Most of convicts were male; female accounted for 15%. Since the formation of federation in 1901, Australians and historians have tried to trace back their ancestors in order to redefine the national identity. Therefore, many debates around the origins of convicts have emerged and developed through years. Two major debates are 'who were the convicts' and the small group of 'convict women'.

In terms of the identity of convicts, in 1956 Manning Clark argues most of them were from a professional criminal class and they enjoyed idleness even when they were serving their sentences in Australia. He points out that most convicts were young workers from towns of England and Ireland. Moreover, the crimes those convicts comitted were causal crimes like theft. A paradox of Clark's persepective is that he says convicts were lazy and not industrious; but he also claims that they all specialised in certain skills.

|

| Manning Clark (March 1915 – 23 May 1991), "The most famous Australian historian". (Source: http://www.penguin.com.au/contributors/manning-clark) |

|

| An evil and t and disordered convict society and the early days of settlement in the Hawkesbury. Just as what Manning Clark described. (Source: http://www.victorking.com.au/index.php?p=1_4) |

However, in 1920s, George Arnold Wood—history professor from Sydney University—states that most convicts were 'village Hampdens' who were more sinned than against sinners. Wood promotes liberalism, so he favours and sympathises convicts. The last Governor of New South Wales—Lachlan Maquarie—used to portray those convicts as 'children of misfortune'. Wood also points out that those convicts were just the victims of bad economies, unfair and hierarchical English society. In a society where aristocracy dominated social resources and jurisdiction, people from working class were very often forced to steal food and daily necessities in order to survive and feed family. The real criminals were ruling elites who collaborated with each other to exploit plebs. Some so-called felonies at that time are even considered as misdemeanour today.

|

| Early Australian convicts were badly whipped as punishment. It was only part of the dark life. (Source: http://www.convictcreations.com/history/larrikin.htm) |

|

| Two convicts were locked in chains. (Source: http://museumvictoria.com.au/accessallareas/discoverycentre/?tag=/idc&page=4) |

Regarding the convict women, Manning Clark and early historians usually reagard them as evil and whore. This whore stereotype of female took root in early convict generation of Australians. During 1960 and 1970, feminist historians like Anne Summers and Miriam Dixson tried to subvert this traditional impression on convict female by arguing that the vices of females were made by convict males and convict society. Summers says convict women were mainly treated as sexual objects in the colony; and even during the journey of transportation, they were sexually abused by male convicts. Later, female and male convicts were loaded separately. In order to survive and avoide harassments, few lucky women gained protection from colonial officials by marrying or serving them. Furthermore, Summers states that female convicts were not as evil as what people depicted even back the days they were in Britain. They just committed misdemeanour such as theft. When they were transported to Australian colony, most of them did not commit further crimes. However, they were treated terribly by being incarcerated in specific female factories like Cascade Female Factory and Parramatta Female Factory.

|

| Cascade Female Factory, a prison for convict women in Tasmania. Female convicts served sentences by working here. There were different layers of female convicts. Some might be able to get married to get out of the factory. Some were mistreated. (Source: http://www.cascadeview.com.au/location.html) | | |

|

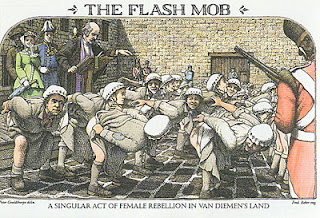

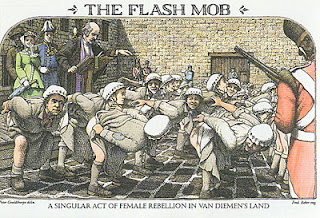

| Later, female rebellion against the unfair treatment in Tasmania. (Source: http://www.convictcreations.com/history/femalefact.htm) |

It was also noticeable that most convicts gained emancipation through good behaviour; and later those people contributed a lot to the development of colony.

No comments:

Post a Comment